We should stop calling ChatGPT and other generative AI software “artificial intelligence,” according to Stallman, because “there’s nothing intelligent about them.”

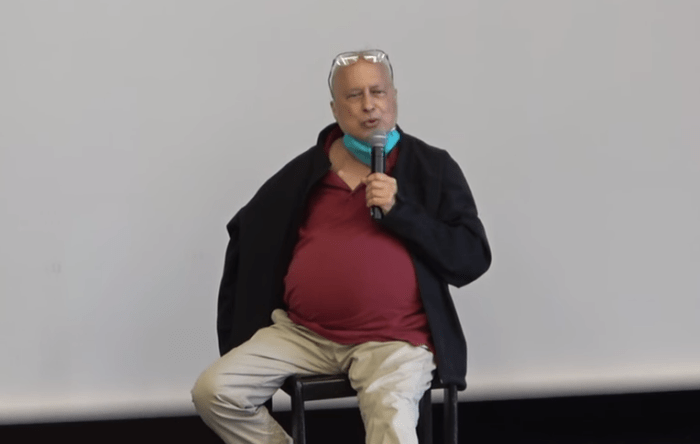

Oddly, the single keynote address at the event to celebrate GNU’s 40th birthday in Biel, Switzerland wasn’t scheduled at the start of the day, but in the early afternoon, at 2 pm local time. This eccentric scheduling only seemed to make sense, given the fact that the speaker was Richard Stallman, GNU’s founder who has always marched to his own beat.

Officially billed as a “hacker meeting,” Biel’s GNU community pretty much pulled out all of the stops for a relatively small one-day event. The speakers’ roster included the likes of Nextcloud co-founder Björn Schießle who talked about “The Next 40 years of Free Software”; Matthias Kirschner, president of FSFE who opened the day with “The FSFE’s Work: An Overview for Free Software Hackers”; and Swiss Parliament member Jörg Mäder, who was on hand to talk about GNU Taler, GNU’s privacy-aware online payment system.

In all, the day was filled with 14 presentations if you include Stallman’s middle of the day keynote.

RMS Takes Center Stage

I could be wrong, but my guess is that despite the impressive speaker’s list, for many in attendance, RMS’s appearance was the event’s centerpiece. That’s interesting, considering that several years back it appeared to many of us as if Stallman would spend the rest of his life in exile. Perseverance evidently pays off.

His talk was short, lasting only about 25 minutes. Except for the big reveal at the beginning about his having cancer, it was pretty much a classic RMS talk, with a focus on Red Hat, artificial intelligence, and why kids don’t think free software is cool (hint: it has to do with wanting to be popular, which evidently was never an issue for Stallman).

This being Stallman, “free software” ruled the day, with the phrase being uttered 13 times during his 25 minutes. “Open-source,” on the other hand, wasn’t spoken even once.

Red Hat and the GPL

After a brief mention of his current bout with cancer (at the event he said that he has “a kind of lymphoma,” but later in the day clarified on his website that he’s being treated for follicular lymphoma, which he called “slow-growing and manageable), Stallman talked about Red Hat’s support contracts, which forbid customers from distributing Red Hat’s open-source software. He said the practice might not violate the GPL (“I don’t have a conclusive answer to that”), but that its approach is “antisocial.”

“They’re threatening to cancel support contracts for users that do what they’re supposed to be able to do, which is to redistribute the free software they’re getting from Red Hat, and this Red Hat should stop,” he said. “There’s a separate aspect, which is that support customers have to pay based on how many users are getting the support and how many machines the support is for. That’s a secondary issue that I don’t think is remarkable. The crucial thing is that they’re trying to stop users from redistributing the software, since redistribution is what it [the GPL] is for. I hope the community’s influence will make Red Hat change that aspect of contracts.”

There’s Nothing Intelligent About Generative AI

When it comes to artificial intelligence, especially of the generative ChatGPT variety, Stallman seems to think that much of the danger is coming from the narrative that the AI marketers are weaving.

“As I see it, ‘intelligence’ needs something like the ability to know or understand some area,” he said. “If something can’t actually understand things we shouldn’t say it’s intelligent, not even a little intelligent, but people are using the term artificial intelligence for bullshit generators.”

He said that systems like ChatGPT “don’t understand anything and don’t know anything.”

“The only thing that they’re good at is making smooth-sounding output, any part of which could be bullshit,” he said. “You can’t believe it ever — well, you’re dumb if you do — so I won’t call those ‘artificial intelligence’ or anything with the word ‘intelligence’ in it, because that encourages people to think that what they [generative AI programs] are saying is not bullshit. It encourages people to believe them, and that gives them the chance to do great harm.”

This doesn’t mean that Stallman thinks that true artificial intelligence doesn’t exist, however. He says it does, and that it’s being used both to make a positive difference in the world, as well as to line the pockets of tech shysters with self-serving intent.

“There are programs that can look at a photo of some magnified cells and tell you, with greater likelihood of being right than any human doctor, whether it’s cancerous or not,” he said. “There are artificial intelligence systems that can very effectively figure out what’s going to attract people’s attention. These are used by anti-social media platforms, and sad to say, they work very well. They’re very good at what they do, but what they do is get users addicted.”

RMS and Ethical Software Licenses

It shouldn’t be surprising that RMS doesn’t appear to be a supporter of so-called “ethical” software licenses, that attempt to regulate who can use software, or for what purpose. It’s “not surprising,” because the first of Stallman’s four essential freedoms that serve as the backbone of the free software philosophy he advocates is the freedom to run software anyway the user wishes and for any purpose.

He didn’t specifically mention ethical licenses by name during his talk, but they were definitely inferred when he discussed ways of dealing with the dangers that artificial intelligence pose.

“We have to realize that if there are things we don’t want programs to be used for, the way to achieve this is by making it illegal to use programs to do that,” he said. “Software licenses are not the right way to prevent a program from being used harmfully. That’s not what software licenses are effective for. They’re not powerful enough to achieve that goal. And because they’re chosen by private entities, it’s undemocratic for those choices to be made by those private entities.”

Stallman said that in cases where the use of software poses a social threat, that use should be regulated by the rule of law rather than by software licensing.

“It’s legitimate for democratic countries to pass a law saying you can’t run a platform designed to maximize users engagement,” he said. “It’s not legitimate for someone who wrote a program and published it to put on it a license with that same condition, because private entity shouldn’t have this type of power over other entities, over people.”

“This is not the first time we’ve seen people try to do this. There are various software licenses that people publish that restrict what a program can be used for, and they always do wrong,” he added, and pointed to an article he wrote on the GNU website about this aspect of ethical licenses some time back. “The situation is unchanged. The real problems of AI, the harmful uses like deep fakes, they should be prohibited by law, and individuals should not make these laws but governments should.”

So what about Stallman’s “bullshit generators,” the ChatGPT-style generative AI programs that can’t be trusted to tell the truth or not hallucinate? They should be regulated too, according to Stallman.

“One thing is perhaps a labeling requirements,” he said. “Publishing any outputs made by a bullshit generator or in part by a bullshit generator should have to have a label saying ‘this was generated by a language model, don’t believe anything is true.’ That might help. And in general, not calling it artificial intelligence, not supporting the belief that they’re anything but gobbledygook. Expecting to find errors in whatever they say, this will help society become somewhat resistant to the harm that they can do.”

Getting Youngsters Interested in Free Software

Towards the end of his talk, Stallman wandered into territory that offered a glimpse of insight into his lack of social skills that have been extensively covered by the press, discussed on social platforms, and which Stallman himself offered as an excuse after controversial comments he made in 2019 about one of Jeffrey Epstein’s victims led to his temporary resignation from the board at the Free Software Foundation, an organization he founded in 1985.

“How do we get young people interested in free software?” he asked, calling the question “one of the conundrums we face in our community.”

“Children sometimes can get interested in free software,” he said as an answer to his own question. “I’m afraid that there is a problem that happens once the calamity of peer pressure sets in. I was safe from peer pressure. I was completely out of popularity. I gave up on trying to be popular. I just said it’s a waste of time for me to do anything trying to be popular so I won’t bother, and so I was safe. And there are some others who are safe.

“Maybe we can find them and interest them in free software so that they can find a community of people that is not so superficially focused on imitating everybody before everybody else imitates each other. Maybe. But we can also look at the anti-social media platforms that exacerbate this affect, the platforms on which people are trying to compete with each other to do stupid things, and all the other terrible effects that they have, which include causing psychological illnesses, suicide, lunacy, terrible suspicion of each other… I don’t have children, I don’t work with children, but I read about these things and they sound pretty damn horrible.”

By this point he had come full circle, and Stallman was back to being Stallman.

“Maybe if we prohibited recommendation engines that are designed to encourage people to be more engaged in whatever platform they’re on, all these problems might become less,” he said. “There is no reason in the world why these companies should be allowed to do whatever profits them the most, and designing their recommendation engines to suit their desires is not what we have understood freedom of expression to mean.

“It’s not really expression of anything. It’s freedom of manipulation; freedom of engineering people’s brains to be ideal victims. Maybe that’s something society needs to prohibit.”

Christine Hall has been a journalist since 1971. In 2001, she began writing a weekly consumer computer column and started covering Linux and FOSS in 2002 after making the switch to GNU/Linux. Follow her on Twitter: @BrideOfLinux

Excellent article. Couldn’t agree more with Dr. Stallman. Wishing him good health and a quick recovery.

“It’s not legitimate for someone who wrote a program and published it to put on it a license with that same condition, because private entity shouldn’t have this type of power over other entities, over people.”

Really? Of course they can. Without this ability, AGPL/GPL would not be a thing. These licenses put restrictions on how and where the software can be used and what state that other software must be in, in relation to the first. One might argue that the code is not the program, but I think that is splitting hairs. The only valid license, based on this, would be MIT.

Other than a few noteable exceptions, open source projects aren’t working as he envisioned. The XKCD cartoon captured this perfectly in this cartoon: https://xkcd.com/2347/.