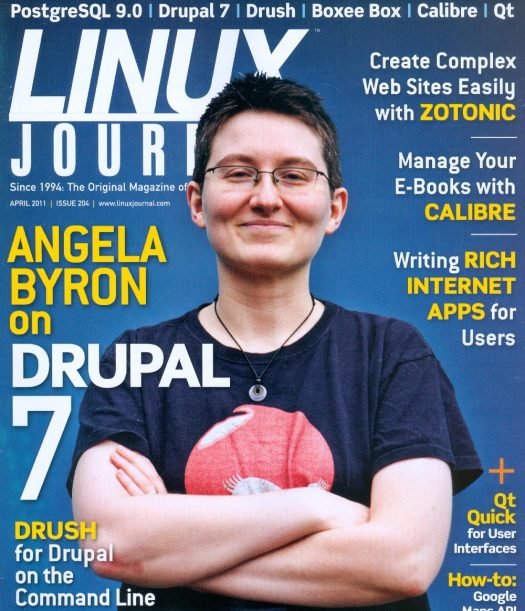

Part of the Linux culture for nearly as long as Linux itself, Linux Journal has announced that its November edition was its last.

Linux Journal is no more. On Friday, publisher Carlie Fairchild wrote that unless “a savior” rides in to save the day, the magazine born in 1994, just two years after Linus Torvalds posted that he was working on an operating system, has already released its last issue.

This is a publication that’s been with us since before the data center discovered the little operating system that can and before the internet forever changed the publishing industry. Linux Journal started its life printed on dead trees, and until relatively recently was delivered to subscribers’ homes by mail or purchased by non-subscribers at the local newsstand.

It started in a time when “open source” was not yet a term. Linux and the GNU stack were “free software,” with the mantra “free as in speech, not as in beer” oft repeated lest anyone confuse software licensed under the GPL with “freeware.”

“It looks like we’re at the end, folks,” Fairchild wrote in the Journal’s funeral notice. “If all goes according to a plan we’d rather not have, the November issue of Linux Journal was our last.”

The problem, of course, is money — or the lack of it — a commodity that she admits has always been in short supply at a publication that “got to be good at flying close to the ground for a long time.” The lack of money, she points out, was made worse by the Google supported modern advertising model in which advertisers no longer support publications “because they value its brand and readers.”

“[T]he advertising world we have today would rather chase eyeballs, preferably by planting tracking beacons in readers’ browsers and zapping them with ads anywhere those readers show up,” she said.

Finances are so bad that current subscribers won’t be getting a refund, although Linux Pro Magazine is picking up some of the slack by offering LJ subscribers six free issues of their magazine. In addition, Fairchild said, “We also just finished up our 2017 archive today, which includes every issue we’ve ever published, including the first and last ones. Normally we sell that for $25, but obviously subscribers will get it for no cost.” She said subscribers will receive an email about both offers.

In a follow-up article published the same day, Linux Journal writer Kyle Rankin, who joined the publication a decade ago, pointed out that the community surrounding Linux and open source has changed over the years.

“We’ve won on so many fronts, but we’ve also lost our way,” he wrote. “It would have been unthinkable and scandalous even a decade ago for a presenter at a Linux conference to use Powerpoint on Windows, but you only have to count the Macbooks at modern Linux conferences (even among the presenters!) to see how many in the community have lost the very passion for and principles around open source software that drove Linux’s success.

“A vendor who dared to ship their Linux applications as binaries without source code used to get the wrath of the community but these days everyone’s pockets are full of proprietary apps that we justify because they sit on top of a bit of open source software at the bottom of the stack. We used to rail against proprietary protocols and push for open standards but today while Linux dominates the cloud, everyone interacts with it through layers of closed and proprietary APIs.”

Rankin makes a good point, which suggests another reason behind the journal’s demise might be that time and history have left it behind. That’s a sobering thought to those of us who adopted Linux not merely for technical reasons, but because we believed the free software FOSS model essential to the future of data technology. As recently as a decade ago we seemed the be the majority of Linux users, even when including commercial users. Today we appear to be a small minority.

On Saturday Noah Meyerhans, a Linux systems engineer for Amazon Web Services, wrote a farewell blog to Linux Journal in which he noted the importance the magazine had in his life during the late 90s when he had been a college student pursuing a computer science degree. Like Rankin, he notes that times have changed, but he prefers to see gains instead of losses. From his vantage in the commercial world, Linux and open source are clear winners. In this sense, he represents the modern paradigm, in which open source is seen mostly as an efficient way of developing software.

“It’s been a long time since I paid attention to Linux Journal, so from a practical point of view I can’t honestly say that I’ll miss it,” he wrote. “I appreciate the role it played in my growth, but there are so many options for young people today entering the Linux/free software communities that it appears that the role is no longer needed. Still, the termination of this magazine is a permanent thing, and I can’t help but worry that there’s somebody out there who might thrive in the free software community if only they had the right door open before them.”

That is, indeed, cause for concern.

Christine Hall has been a journalist since 1971. In 2001, she began writing a weekly consumer computer column and started covering Linux and FOSS in 2002 after making the switch to GNU/Linux. Follow her on Twitter: @BrideOfLinux

“there are so many options for young people today entering the Linux/free software communities that it appears that the role is no longer needed.”

The entity we call the “users group” could be a thing of the past for the same reasons. Any users group that charges a fee for membership has to ask “what do we offer that is not available for free on the Internet?” This is true of groups that do not charge a fee as well.

Wait a minute!!! We should not get too carried away on “thing of the past” frame of mind because there are more Linux magazines today than there ever were before. The two originals are gone but we still have at least three other Linux magazines on the magazine racks plus the Raspberry Pi offerings. Ubuntu, PCLinux OS, Fedora, and Free BSD all have their own e-mags that are a free download.

The challenge for computer interest magazines and user groups is to be a focal point for new and interesting information.

Best regards

John Eddie Kerr

Guelph, Ontario Canada

I have experienced this before. Maximum Linux magazine was my favorite subscription and they stopped after a year. The Linux Gazette was my favorite online magazine, and they never even said farewell.

So many Linux books, haven’t been published/updated in years (like a better Slackware manual, then the one Slackware provides in print form).

User groups that break up, and still advertise online.

Schools that have gone out of business, that were the only ones to teach Linux specific classes.

The internet makes it easy to learn at odd hours (it is after midnight as I post this), and today’s phone tech, makes it easy to reach across the world and contact someone, but we have lost so much of the sense of local community is both Linux and real world, IMHE (know your neighbors?).

Gone, just like so many distro’s, and things go on.

LJ was a printed publication, I subscribed to it just because of that from the beginning until the end of that era. Bringing the physical papper with me was 100% the experience. I don’t regret stopping my subscription as I wanted the papper-edition not the on-line version.

I subscribed to the LJ back in the late 90’s and early 00’s, and I remember when Nick Petreley took over just about the time Microsoft started to ramp up its attacks on Linux via the SCO proxy. Petreley did everything he could to alienate the readership: Changed the physical format of the journal, ousted some of the long-term contributors (Marcel Gagne ?), gave an inordinate amount of column space to John “Maddog” Hall, and in general decreased the quality of the material in the journal as much as he could. It worked, and the LJ never recovered it lost readership. It then moved to digital-only format and try to prolong a slow death, but let’s not ignore the effect of that one blow to the head that was Nick Petreley’s reign in charge of LJ.

Lots of truth to what she says. The Linux community used to be vocal and dedicated to keeping things open and free. Not so much anymore. The limp response to Microsoft’s Secure Boot lockout convinced me that the community was dying quite a while ago.

I recently upgraded to the most recent Ubuntu only to find a tool I relied on, x11vnc, was shipped with a critical bug rendering it unusable. Sloppy. The pointless desktop war was mutually destructive, and focus on everything else was lost.

Take a look on any Linux news site and what is newsworthy? Containers. Microsoft support. More containers. Yawn. Gone is the DIY spirit, the roll it yourself nature.

The last big push on the Linux world was systemd, and that was an ugly and forced affair.

It hurts to see ANY publication/distro/service or product that comes from the FOSS and open source community “pass away”. I have had my share of tearful moments when some of my favorite distros also gave up the ghost (Fuduntu…PearOS….and a slew of others!) But While the past is filled with sorrow for all its goodbyes? We also have other things to look at. New distros, new technologies etc. I do agree with most of the sentiment here, there’s too much “integration” going on with MS and Linux, and while there are some Windows Admins that might find this a great thing, the “Linux Pure” should be up in arms, not because of fanboy-ism, but because that was the true spirit of Linux! the whole “Windows Not Needed” the rebellious and risk-taking attitude of the devs and programmers who made x0rg, Gnome, and all the other toolkits needed to have a functioning version of Linux running on your system. And while I might be guilty of running OpenSuSE or Ubuntu MATE, I’m also learning programming and coding so that I an strip the things from these OS’es that are considered proprietary, or non-free.

The first thing I see is a link to another article ranting about RMS being a lunatic. The article itself starts by sneering at the free software movement, then ignores the role it played (remember, Torvalds wrote an operating system) only to end by lamenting the demise of political reasons to use “open source” software. In quotes, as the term was invented to get rid of the political aspect of free software!

So maybe the distinction between free software, open source and freeware is important after all?

Free software is political.

Open source software is deliberately unpolitical.

If you drown out political and social aspects of software, don’t complain if nobody cares about the political and social aspects of software.

And if you fight for a better society you *will* look like a lunatic.

Linux Journal not dead after all:

https://www.linuxjournal.com/content/happy-new-year-linux-journal-alive