Three resignations from important posts at the Apache Foundation in May point to a generational change that is happening at other Linux and open source organizations as well.

“It is with a mix of sadness and appreciation that the ASF Board accepted the resignations of Board Member Jim Jagielski, Chairman Phil Steitz, and Executive Vice President Ross Gardler last month.”

When this showed up on the FOSS Force Newswire early this week under the heading “Statement by The Apache Software Foundation Board of Directors,” my mouth literally fell open.

Uh-oh, I thought. This doesn’t look good.

Without thinking twice, I immediately pinged Jim Jagieski using the private messaging feature on a social site. Jagieski has been with ASF since the beginning, serving on the board every year except 2018, many of them as chairperson, and pulling duty for several years as the foundation’s president.

I also know him to be a straight shooter, so I figured he’d let me know if something was up, even if he couldn’t tell me the whole story.

“What’s up with all of the resignations at ASF?” I asked. “If it had just been you or someone else I’d give it no mind, but so many at once means I gotta wonder.”

Jagieski took the conversation to email and wrote, “Although the number of people seems high, it really isn’t a sign of deep troubles.”

At about the same time, Roy Schestowitz, the publisher of Techrights and Tux Machines, posted something that seemed to imply that the three who’d resigned were somehow and ominously connected to Microsoft. This wasn’t much of a surprise, since Schestowitz is prone to still see Microsoft conspiracies at every turn — which is fine in my book because continued accusations from the open source community, even if unfounded, probably helps keep Microsoft as honest as it’s possible for a giant corporation to be.

Unless he knows something I don’t, however, the facts don’t entirely fit Schestowitz’s accusations.

It’s true that Gardler has worked for Microsoft, since 2013. He started as an evangelist and currently works as a principal program manager with the Azure Container Service. He’s also been a big part of the Apache Foundation since 2000, long before he took employment at the Redmond campus. At various times he’s filled the roles as ASF’s president and director, as well as the EVP position from which he just resigned.

He’s also a dyed-in-the-wool Linux user, which I discovered back in 2016 when I pinged him to see if he could answer a few questions for an article I was writing for what was then a Windows-oriented website.

“I don’t know anything about Windows, I’m afraid,” he pinged back. “I’m a Linux guy.”

As far as I know, neither Jagieski nor Steitz have any major connection with Redmond — not that it would matter if they did. There’s no mention of Microsoft on either’s LinkedIn resumes, with Steitz’s going back to 1990, and Jagieski’s all the way to 1983. Besides, I see no reason why there would be a connection between the former Evil Empire and the resignation of three people from important positions at ASF.

According to Jagieski, none of the three have left the foundation; they just resigned from positions they were holding.

“Ross gave up being EVP because he felt he could be more effective as a regular member than as EVP,” Jagieski said. “Phil left because he didn’t have the time to put into it and he didn’t realize that until after the election.”

Steitz’s lack of time was due to a career move he made in February of this year when he signed on as CTO at the Arizona-based VoIP startup Nextiva. With Gardler there might be a slight Microsoft connection, as I’ve heard he might have been concerned that any expression of his personal opinions might be taken as representing the official opinion of the foundation. Again, anti-Microsoft sentiment continues to persist in the open source community.

Later that night, Sally Khudairi, the foundation’s VP of marketing and publicity, told me “there’s nothing nefarious here.”

“With our membership growing, it’s natural to have new participants in leadership positions, including the board,” she said. “Changes in our leadership at this time gives us the opportunity to explore new directions in addressing long-term foundation needs.”

The “new participants in leadership positions, including the board” turns out to be key here, and confirmed something else I’d heard from Jagieski. ASF is experiencing something of a generational change.

ASF was founded in 1999, meaning it turns 20-years-old this year, the span that’s often used to denote the length of a human generation. It appears that the inevitable eventuality of a changing of the guard is at play, as younger board members, some of whom were still children when ASF was founded, are now replacing a leadership that’s been in place since the foundation’s beginning.

“I guess a lot of the ‘churn’ at the ASF is kind of matched with what is going on in the open source ecosystem in general,” is how Jagieski put it. “In both cases it’s being a young adult and trying to figure out what we want to be when we grow up, so to speak, which is especially hard when you have pressures, internal and external, pushing and pulling, at times in different directions.”

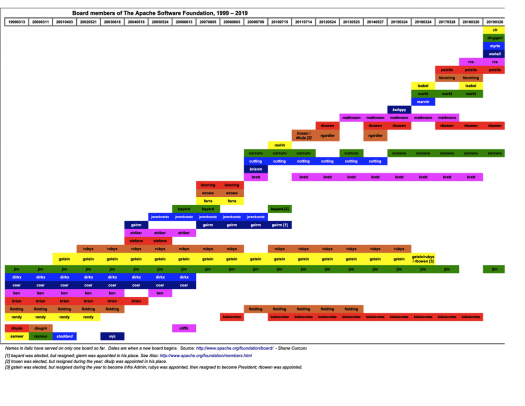

Even a quick glance at a block chart of ASF board members since the foundation’s inception reveals an obvious change in the character of the organization’s board in recent years. If the two resignees are removed, this year’s board came to the table with a total of seven years previous experience serving on the ASF board. Compare that with 2009, the mid point between the foundation’s birth and today, when the board being seated had a collective 29 years previous experience.

There are pros and cons to such a situation. One positive is that younger board members who grew up connected to the internet instead of three channels of black and white television and AM radio will bring different perspectives and different ways of thinking, simply because of their different life experiences. But younger members will also lack firsthand institutional knowledge of an organization’s traditions and history, which can be especially problematic from the perspective of someone who’s been around since a project’s inception.

“I think that Apache is best served, and best serves the community we represent, when we stay true to our original goals and ideals, our principles, so to speak,” Jagieski said. “But that set of tenets, what we call The Apache Way, can be kind of hard to grok for some people, even ASF members. So while some, with good intentions, think that open source needs to be ‘redefined’ to match the world we are now in, some feel that Apache should do the same.”

The two resigning board members have been replaced by Danny Angus and Ted Dunning, who collectively have nearly two decades of experience at the foundation, which will help compensate for the experience lost with Jagieski’s and Steitz’s absence. Angus, who works as the senior manager of software development at Amazon’s Prime Video, has not previously served on the board, but he’s been involved at ASF since 2001 and is currently VP of Apache Labs. Dunning, CTO at MapR Technologies, has served as a Project Management Committee member for the ASF projects Zookeeper and Mahout since 2007. In addition, Jagieski, Steitz, and Gardler will remain available for board members seeking advice or mentoring.

ASF isn’t the only Linux and open source organization experiencing a paradigm shift as leadership shifts from an old to new guard. At Open Source Initiative, where I am currently serving as a first term-board member, this transition has been made easier by the fact that the organization’s leadership prepared for the change.

“The OSI Board has undergone a conscious, managed transition over the past eight years, which I’ve played a significant role in devising and leading and hope to finally step back from next March,” Simon Phipps, OSI’s president, told me. “The Board that set this in motion under Michael Tiemann deserve a lot of credit too for their vision and trust.”

According to Phipps, instead of prolonging the inevitable, OSI took steps to hasten and welcome new blood with new ideas to the organization.

“Around 2010, the board members decided to make room for a new approach to leading OSI and introduced both term limits and a stakeholder membership (affiliate organizations and individual open source advocates) to select replacement directors,” he explained. “The new board was arranged so that no one constituency could take control, and it was fully expected that the result would be a more varied board membership.”

At OSI, forcing the change to the next generation of leaders early in a controlled fashion seems to have smoothed some of the bumps that are currently an issue at ASF.

“The term limits ensured the long-term leadership had to change, but phased over several years so there was no sudden shock,” Phipps said. “We also funded and recruited a staff so that the organization had stable operational oversight despite the regular changes in directors. As a result, we have seen a younger, more diverse board gradually elected, with the consequence that today’s board is younger than ever while still retaining older voices.”

Although the ASF made no such preparations, it seems that the organization is helping it’s new guard find itself by getting out of the way.

“This new board had a vision that was different enough from mine that I didn’t want to be a constant thorn in their side, and they deserve that chance to try things out for themselves,” Jagieski said. “I’m still there, helping where I can, as I can, more as an adviser than as a leader; providing background, history, experience and guidance.”

Christine Hall has been a journalist since 1971. In 2001, she began writing a weekly consumer computer column and started covering Linux and FOSS in 2002 after making the switch to GNU/Linux. Follow her on Twitter: @BrideOfLinux