Our delve into the numbers presented by Distrowatch indicate that although there have been some notable changes over the last serveral years, the Linux ecosphere is mostly stable from a distro perspective.

Free software is so diverse that its trends are hard to follow. How can information be gathered without tremendous effort and expense? Recently, it occurred to me that a very general sense of free software trends can be had by using the search page on Distrowatch. Admittedly, it is not a very exact sense — it is more like the sparklines on a spreadsheet that show general trends rather the details. Still, the results are suggestive.

As you probably know, Distrowatch has been tracking Linux distributions since 2002. It is best-known for its page hit rankings for distributions. These rankings do not show how many people are actually using each distro, but the interest in each distro. Still, this interest often does seem to be a broad indicator. For instance, in the last few years Ubuntu has slipped from the top ranking that it held for years to its current position of fifth, which does seem to bear some resemblance to its popularity today.

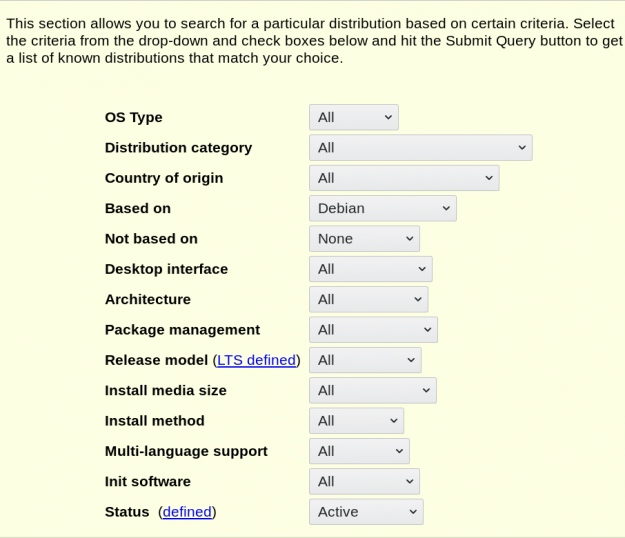

However, Distrowatch’s search page for distributions is less well-known. Hidden in the home page header, the search function includes filters for such useful information as the version of packages, init software, and what derivatives a distro might have, and lists matching distros in order of popularity. Although I have heard complaints that Distrowatch can be slow to add or update the distros listed, it occurs to me that the number of results indicates general trends. The results could not be plausibly used to suggest that a difference of one or two results was signficant, but greater differences are likely to be more significant.

Let me give you some examples of how these search results might be meaningful.

If you search for distributions based on Raspberry Pi you get 34 results, with major distributions like Manjaro, openSUSE, Arch Linux, and Kali the most popular. By contrast, the only result for Android is Androix-x86. From these results, it seems reasonable to conclude that the Raspberry Pi continues to be popular, because 34 out of 278 distributions listed in total is a reasonably high number. At the same time, the interest in porting Android to Linux seems low. The only group interested in the report is a sub-project of Android itself.

Similarly, using the Nosystemd filter returns 100 results. That number suggests that, while a majority have accepted Systemd, a large minority has not, especially since the most popular systemd-free distribution is MX Linux, which also currently tops the page views on Distrowatch.

In the same way, the Release Model filter returns 234 distributions that do fixed releases, compared with 48 that do rolling releases, and only 15 that do long term support releases. Unsurprisingly, those that do LTS releases are among the most consistently popular releases, such as Debian, Ubunu, and CentOS.

Yet another example is the Package filter. Results in December 2019 show DEBS are used by 126 distributions, close to four times those of any other package management system. RPMs, the dominant package manager around the turn of the millennium, receive only 38, showing how it has declined in popularity. The newcomer Flatpak receives 39, while its rival Snap is virtually tied at 36. Whether these numbers reflect a dissatisfaction with RPMs cannot be said, but the results do show that while there is an interest in them, neither newcomer seriously challenges DEBS — at least, not yet.

Derivative Distributions

Some of the most interesting results are about derivative distributions. Only 62 are independent or original distributions. Mostly, the independents are major distributions, like Debian, Fedora, and openSUSE, although the relatively small Solus and PCLinux0S distributions are also in the top five. That means that almost 78% of the 278 active distributions today are based on another distribution, a figure that raises questions about originality and redundant effort. On the surface, Linux distributions appear diverse, but in reality, much of that diversity is deceptive.

As the figures for package managers suggest, 122 of the listed distributions are based on Debian. Add to this derivatives of influential Debian derivatives such as Ubuntu ( which has 55) and Linux Mint (with one), and some 70% of active distros are Debian-based. Moreover, only eight Debian derivatives are based on Debian’s Testing repository, and two on Unstable. These figures seem to suggest that Debian is preferred by a majority for its stability. For all that people sometimes complain about Debian’s lack of cutting edge software, apparently reliability is what most people want — or, at least most people who build distros.

After Debian and Ubuntu, the sources for derivatives are much less influential. Fedora and Red Hat Linux are the source of 21, and Arch of 20. Gentoo, which had a following of experts came next with 11, then Slackware with 7. The once popular Mageia and Mandriva lacked derivatives altogether. It’s a situation that would have been unthinkable for any of these distributions a few years ago.

Long Term Trends

Distrowatch’s search page is an indirect indicator of Linux trends. However, none of its results are startling, so I am cautiously prepared to trust it, so long as not too much is made of small differences. But what about long-term trends?

In 2014, I noted that the number of active distributions had declined in the three previous years, falling from 323 to 285. In 2019, that number had fallen to 278. Technically, that meant that the decline had continued, but at a rate of just over one distribution per year. A lost of 38 seemed potentially significant in 2014, but a loss of 7 in five years seems too small to be significant. It would seem more accurate to say that in the last five years that the number of distributions had stablized more or less, being no cause for alarm.

Similarly, while the number of Debian derivatives has declined by 5 since 2011, that is even less than the number of active distros has. Accordingly, it seems safer to say that the number of Debian derivatives remains stable. By contrast, Ubuntu’s numbers have dropped a quarter from 74 in 2011, and Fedora’s and Slackware’s have also dropped.

The areas to watch, I think, are the other filters. Will the init software, release model, or package management figures change? Maybe in a few years from now I’ll check.

Bruce Byfield has been involved in FOSS since 1999. He has published more than 2000 articles, and is the writer of “Designing with LibreOffice,” which is available as a free download here.

I used Distrowatch from the time I decided to use Linux. One problem is one Man distros or those with small teams. I actually started with the original Solus, and when that disappeared went to Point. Both disappeared rather quickly, though Ikey revived Solus as an independent distro, I no longer trusted it would continue. At that point I switched to dual booting Debian Mate for stability, and Ubuntu Mate for things like watching videos as it stays more up to date. I see less distros as a good thing, giving more support to major distros that you can depend on.