In March 2024 Bruce Perens released a first draft of his “Post-Open License,” which would require large companies using Post-Open software to pay a fee, while individuals and nonprofits will be able to use it for free.

By any standard, FOSS dominates modern computing. What were fringe movements thirty years ago are today mainstream necessities that reduce development costs and reduce time to market. Some estimates suggest that as much as 94% of the Internet depend on FOSS.

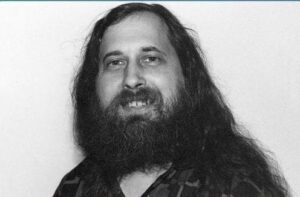

However, according to Bruce Perens, one of the coiners of the term “open source” and a source of the Open Source Definition, “our licenses aren’t working anymore. We’ve had enough time that businesses have found all of the loopholes and thus we need to do something new.” In the past few years, Perens has been trying to develop that something new. He calls it post open source, or simply “post-open.”

The problems Perens tries to address are not new. As long ago as 2012-13, a short-lived movement used the same term as it tried to deal with the problem of projects that avoided defining a license in order to avoid complications. Perens does not mention this earlier movement, but in his writing on the subject,he does mention several current problems with which he has been personally involved, such as:

- Companies like Red Hat and OS Security do not make source code freely available, adding extra requirements not covered by licensing.

- Products like Apple iOS or Google Android that use open source for development but release apps that are mostly proprietary.

- The attempt to add terms to licenses that don’t allow additional terms, as can easily happen with the software-as service GNU Affero General Public License.

- The indeterminate status of AI output, particularly with its training data.

To which might be added the tendency to invoke the prestige of FOSS without using FOSS licenses. For instance, Mark Zuckerberg discusses Meta’s Llama AI as though it’s open source when its license clearly is not. Such misuse threatens to water down open source to meaning simply freely accessible.

The Solution

Perens’ solution is a proposed hybrid license and contract. His idea is that individuals and non-profits will continue to use FOSS for free, but that companies pay yearly for the use of FOSS-licensed software. Compliance for such contracts would be regularly checked, and the payments from companies would go to further FOSS development.

The draft covers:

- The contract files to be shipped with software.

- A listing of derivative works and their current state.

- How revenue is collected and distributed.

- How the contract is terminated.

Perens’ draft is by no means complete. In fact, it omits numerous practical points. As a result, it can make the issues sound simpler than they actually are. To start with, to reform today’s FOSS is apt to be more difficult than the invention of FOSS decades ago, simply because it is more established. Moreover, Perens perhaps exaggerates the failure of modern FOSS. Yes, license violations are expensive and distressingly common, but FOSS does seem able to defend itself successfully, in or out of court. For example, without so much as going to court, the response to RHEL’s licensing restrictions has been the creation of community-based replacements such as AlmaLinux and Rocky Linux. Whether contracts would defend the rights of users is by no means certain. They might only offer more loopholes for the unethical.

A host of other questions also remain. To give a few:

- What organization would collect and distribute contract fees? One for all of FOSS? Or one for each project? How much would overseeing contracts subtract from the money that goes to developers?

- Projects would need to decide how to distribute any money received. How would each developer’s share be determined? The share of leaders? Of non-developers?

- Would companies agree to pay for what they now get for free?

- How would fees be determined? By a company’s financial status? How much it relies on FOSS? Or would there be a flat fee for all companies.

- Many FOSS contributors are employed by companies. Since they already make a contribution, should they get a discount?

- What advantage would companies get? If many decided to walk away from FOSS,a post-open license might ruin FOSS instead of saving it.

An FSF Analysis

Krzysztof Siewicz, Licensing and Compliance manager at the Free Software Foundation, gives Peren’s concept a mixed technical review, suggesting potential dangers and some practical suggestions for implementation, as well as providing a broader context. His comments are worth quoting in full:

- “The post open source assumption that there are some important free software programs that are under maintained, have a steep learning curve, or lack usability, is correct. Whether money is a solution for these problems is not certain, but they correctly identify that having difficulties in obtaining income from writing free software is an issue for at least some developers.”

- “The documents about ‘post open’ posted by Bruce Perens appear to be intended to operate in a manner similar to ‘selling exceptions‘. Maintainers of free software programs would offer ‘post open’ license to those who for some reason do not want to follow the free software licenses. Although, they might also operate as additional terms added to free software licenses, limiting them in scope. It is not easy to determine, because ‘post open’ license drafts… are written with a focus on termination of rights when some conditions occur, but it’s not clear what is allowed to do to begin with.”

- “Assuming that ‘post open’ aims to release those who opt in from following free software licenses, then this would lead to less situations where users are granted software freedoms and provided with source code of software. Such an erosion of the free software movement would be a real threat when more and more people opt in. Clearly, Bruce Perens’s project does not treat software freedom as a priority, to say the least. And it should not be take for granted that even if ‘post open’ results in money for developers, the programs’ maintenance and usability would improve.”

- “As far as the idea of collecting remuneration is concerned, the project appears to come up with an institution similar to a collecting society. These are traditionally recognized schemes for collecting funds and providing authors and artists with a form of income, but they also come with inherent problems (mainly related to difficulties in distributing the funds fairly and transparently). Most likely, ‘post open’ will run into the same problems and unfortunately the documents only vaguely mention popularity as the basis for distribution. The problems aside, it’s not a bad idea as such for providing authors with money.

- Nothing in the operation of a collecting society requires that users are denied their software freedom. Actually, one could certainly imagine a collecting society or a statutory remuneration scheme without undermining software freedom and copyleft. For example, in the continental copyright law there are statutory limitations and exceptions to exclusive rights (such as private copying or the right to use for educational purposes) coupled with statutory right of remuneration. One could imagine states adopting software freedom as a statutory-guaranteed right coupled with similar statutory remuneration scheme. This could address the income problems that ‘post open’ seems to target but would not do it by contracting the software freedom away.

So far, reaction to Peren’s ideas seem muted, so we may never have answers to many of these questions. However, self-examination can only be healthy for paradigm as old and as widespread as FOSS, and debating post-open source may prove useful in itself, even if the ideas are never implemented. If they are implemented, a pilot study or two would make a cautious start.

Bruce Byfield has been involved in FOSS since 1999. He has published more than 2000 articles, and is the writer of “Designing with LibreOffice,” which is available as a free download here.