Firewalls are rising, alliances are fraying, and Europe’s digital future may be written in code untouched by American hands.

Within a month of taking office, Trump’s threats to pull out of NATO, make Greenland part of the US by hook or by crook, and end a traditionally close relationship with Europe to cozy up to Putin were already having an economic impact on the US tech business.

Since then, it’s only gotten worse. His tariffs–and ongoing tariff threats–haven’t made Euro-businesses of any stripe keen to do business with any kind of US business, and EU regulators are threatening to take increasingly harder stances against US tech businesses in efforts to protect the personal data of its citizens under the rallying cry of data sovereignty.

Outside of news reports, where alarms were already sounding, the first evidence I had that Trump was having an economic impact on Silicon Valley was in mid-March, or barely seven weeks into Trump’s second term. During the first day at SUSECon, which this year took place in Orlando, Germany-based SUSE’s CEO Dirk-Peter van Leeuwen and CTO Thomas Di Giacomo took questions at an invitation-only round-table presentation for the press. Not surprisingly, the subject of data sovereignty came up early on.

The CEO offered this response to a question that was mostly generic and broad stroked:

“We are already seeing customers who were at the verge of making certain decisions, who paused them and came to us and said, ‘We want to really re-evaluate all the options.’ Given that we are a European company, in the current geopolitical situation … we see that there is a renewed opportunity for us to play in certain spaces.”

DP, as he’s called, didn’t give away much there, but it told me that just a month and a half in, at least one European tech company was seeing an opportunity to pick up some local business that just a few weeks earlier had been USA-bound.

Again, this was in March, long before the United States started looking like pre-Falklands Argentina, Mussolini’s Italy, or Stalinist Russia.

The Data Economy

In my experience, many if not most Americans don’t realize just how important the tech sector has become, and I totally get why.

It’s also easy to just shrug and consider big tech’s problems as inconsequential. It’s only computer stuff, right? Data. Ones and Zeros stored on some kind of storage device. It’s also just another form of vaporware, as many witnessed after a wave of adolescent hackers took over the hard drives of some of the US’s most protected servers, where one wrong command could make two generations of information go poof!

It’s sort of like The Maltese Falcon, insofar as data is the stuff that dreams are made of. If you’ve seen the movie, you know that a string of dead bodies resulted from following that dream.

“There’s the saying that data is the new oil,” Frank Karlitschek, co-founder and CEO of Nextcloud, said near the beginning of a small online press event in late May. “What’s meant here is that oil is like the fundamental building block of the old economy, and the idea is that now — and I think this is correct — data is replacing this going forward. This is an interesting statement, because we all know how many conflicts and tensions were created by oil, and by countries and places on the planet where oil is coming from.”

Like SUSE, Nextcloud is a Germany-based open source company. Its chief product is an eponymous self-hosted cloud platform that lets companies handle much of their computing needs in-house, without having to rely on the likes of Microsoft, Zoom, or Dropbox. Among other things, the platform helps to solve one of the thorniest issues facing European business, which is data sovereignty, or making sure that customer data that’s collected in Germany stays in Germany — or in any other country where data is collected.

“This raises the question, if oil is replaced by data, where is the data?” Karlitschek continued. “Where is the data stored? Where is the actual cloud? Where are, maybe, the potential conflicts of the future?”

The vast majority of the clouds storing the collected data of EU and UK residents are operated by the same US-based tech giants—Amazon, Microsoft, and Google—that dominate cloud services stateside. This includes a significant amount of data from homegrown EU companies such as SAP, Siemens, Deutsche Telekom, and OVHcloud, though some of these firms also use European cloud providers. China’s leading cloud companies (Alibaba Cloud, Tencent Cloud, Huawei Cloud, Baidu Cloud) are also active in the European market, but US-based providers remain by far the most prominent.

Exact figures on the amount of European data being handled by US companies are hard to find. However, the American Chamber of Commerce to the European Union reports that 90% of the EU relies on transatlantic data flows and the US-based think-tank, Center for Data Innovation, reports that 83% of GDPR fines as of 2025 are against US companies.

The US/EU Tech Stare Down

The EU’s concerns about US tech’s dominance in European data management predate Trump.

Starting in 1995, or at about the time that the internet was catching on, data in the EU was regulated under the EU Data Protection Directive 95/46/EC, which required EU countries to create national privacy laws to provide protection for the personal data of their citizens, as well as to establish rules for the transfer of personal data outside the EU.

Under the directive, the data of EU citizens could leave the EU only if going to countries that the EU deemed to have an “adequate level of protection” in place for privacy. Very few countries, including the US, qualified, which in 2000 led to the Safe Harbor Agreement between the US and EU, which allowed US companies to comply with EU data protection standards when transferring personal data from the EU to the US.

For a long while, this arrangement allowed Google, Facebook, and similar companies to legally process and store EU citizens’ data on US servers. That changed when Edward Snowden revealed the extent of US government surveillance—just as the world was finally beginning to heed the warning that the once-innocent “don’t be evil” search engine, Google, had become an advertising giant with an appetite for personal data that rivaled any speed freak’s craving for meth.

In 2015 the EU courts concluded that the Safe Harbor Agreement wasn’t enough, and that EU citizens’ data wasn’t safe from US government access once it physically left the EU. This led the Obama administration to negotiate Privacy Shield, which was basically a continuation of the Safe Harbor Agreement but with added safeguards. Only in effect for four years, the Europeans were never really happy with it, and only reluctantly agreed to it as a compromise.

In 2020, the European Court of Justice declared it invalid, ruling it didn’t provide EU citizens’ data with adequate protection against US surveillance.

In 2023, the EU and U.S. developed a new agreement, the Data Privacy Framework, which was adopted by the European Commission in July 2023 and which allows personal data to flow freely and securely between the EU and US companies that agree to follow strict privacy obligations as spelled out in the framework. Although still in effect, it appears that this agreement might end up having an even shorter life than the one that preceded it.

Trump, Data Sovereignty, Disruption

Without Trump on the scene, it’s probable that we’d be headed for a wash-rinse-repeat cycle as far as DPF is concerned, with the framework being replaced by another updated agreement between the US and the EU. With Trump in the White House, that’s not so certain anymore.

For starters, Trump has been threatening to tear up the agreement, and EU nations might not be in a big hurry to placate him if that happens, since he has managed to alienate not only the leaders of many EU nations, but is widely distrusted by the EU population as well. Indeed, trust in US leadership, as well as in our intentions, are at historic lows and multiple surveys show that Europeans now see us as a “necessary partner” rather than as an ally. The US government’s favorability in Germany, for example, is now not much better than the most unpopular governments in Europe.

A combination of tariff threats, withdrawal from international agreements such as the DPF (along with the gutting of the Privacy and Civil Liberties Oversight Board, which is largely tasked with holding up the US’s end of the DPF), and his transactional approach to alliances have led EU policymakers and the public to view the US as a volatile and unreliable partner.

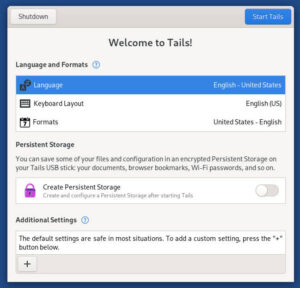

The sentiment in Europe these days is more to constructing solutions that are engineered to meet Europe’s unique needs. This includes building new clouds designed to meet the continent’s specific needs, and dropping other “made in the USA” software solutions for open source software products.

Christine Hall has been a journalist since 1971. In 2001, she began writing a weekly consumer computer column and started covering Linux and FOSS in 2002 after making the switch to GNU/Linux. Follow her on Twitter: @BrideOfLinux

All those uber valuable EU tech companies gonna fill the void – not LOL