From bulletproof backpacks to banning file downloads: why our fight against 3D printed guns keeps missing the point—and what policy leaders should really be asking.

The Register recently reported about the attempts by Manhattan District Attorney Alvin Bragg and other US officials to stop the proliferation of homemade untraceable 3D printed guns. Most of that article is about two things that Mr. Bragg did to tackle this issue, namely:

- He got an online 3D printing library to remove downloadable gun designs.

- He asked a 3D printer manufacturer to ensure its products could detect gun designs and refuse to produce them.

Now, it might be because of my decadent European blood, but I’m weird. Real weird. So weird, I think that things like…

- bulletproof backpacks for children.;

- suggesting guns for teachers (guess who said that?, but he’s not alone) so stressed that they may fire them at parents, rather than school shooters;

- being killed for knocking at the wrong door

…aren’t a way to live. So, since I’m such a nutcase, you may be justified to assume I’d support what Mr. Bragg is doing. Gun control everywhere, 3D-printing included! But you would be wrong.

The Register says that those two strategies are “unlikely to slow the proliferation of 3D printed weapons.” Me, I say that while gun control is good, those strategies are unfeasible and dangerous at the same time, and they aren’t even new.

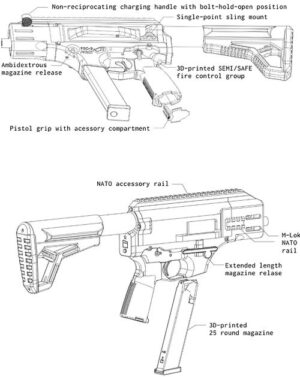

What Mr. Bragg is trying to do in 2025 has been exhaustively researched by me and others, with conclusions that are pretty clear. I studied this topic in 2015, in the context of an EU-financed research on Digital DIY, and the only change I’ve seen in this landscape since then is the addition of explosive-carrying, equally untraceable DIY drones to the list of weapons we should worry about.

If the history of the internet teaches us anything, it’s that attempts to completely remove downloadable gun designs will work exactly like previous attempts to remove porn or illegal copies of music and movies. I’m not saying that certain bans should never be done, but nobody should expect them to have any meaningful positive impacts, and everybody should be seriously worried about the doors they may open. To see what I mean, consider questions like:

- If mere possession of the designs of a 3D-printable firearm is bad, then why should making or storing a digital or paper copy of the web pages returned by a simple web search for 3D-printable guns be any different?

- Why stop at 3D printing, or at the internet? Why not movies? John Malkovich showed how to build an untraceable pistol to millions of people 32 years ago; should we ban “In the Line of Fire”?

- Even the machines to produce firearms, ammunition, deadly drones, and untraceable 3D printers that can produce all those things are available off the shelf or as open source hardware designs. Should those too be banned? Again, where should we stop?

The second strategy — requiring 3D printers to detect and block gun designs — has the same problems, even in different formats. Copy machines can refuse to duplicate banknotes because there are only a few hundred banknote designs; we know exactly what each looks like; and we only care about copies that are so perfect that humans might not spot them as fake. Therefore, telling copy machines that they must “never print anything that looks exactly like this” was relatively trivial.

But making 3D printers that will never print anything that may be any part of any weapon that people may ever invent, including other 3D printers — which is what should happen to make Mr. Bragg happy — is as smart as asking for “smart weapons” equipped with “ethical AI” that refuses to fire at innocent targets. Before you ask: yes, someone had the gall to seriously propose weapons like that — one of the dumbest ideas I’ve seen in years.

At a purely technical level, 3D printers that won’t print weapon parts — or devices to make such parts — are impossible to make, with or without the glorified parrots some call “AI”. Actually, it’s worse than that. In order to give people the illusion that they can’t print weapons, both the printers and their connected computers would need to be so limited as to be worthless (not to mention dangerous for real innovation and democracy). Why on Earth should anybody buy a 3D printer that can only print a small predefined list of objects, or a computer that cannot produce or store “dangerous” files?

Assuming they could ever be successfully made, 3D printers crippled in the way Mr. Bragg wants would be just like Tivoization or mandatory “age verification schemes” (instead of simply never giving smartphones to children). All of these are just different faces of the war on general-purpose computing that Cory Doctorow described in 2011.

There are much better ways to protect people from untraceable 3D-printed guns. These range from developing social policies that would make more people stop wanting to kill others, to exercising more control over the materials needed to make guns at home. Mr. Bragg is late to the discussion, but this gives him a big advantage if he chooses to use it to build on previous research — while ignoring false solutions with no positive effects.

To get a full view of the real dangers of 3D-printed guns, of the wrong ways to control them, and of some concrete solutions, I invite Mr. Bragg and everybody else to check out these posts and papers from the DiDIY project (2015/2017):

- The End of Gun Control

- The Threats of Dangerous Information

- Digitally manufactured weapons: can they be controlled?

- The “DiDIY and gun control” part of the report on Digital DIY risks, synergies and education

Or this 2018 summary by me of the same topics.

Marco Fioretti is an aspiring polymath and idealist without illusions based in Rome, Italy. Marco met Linux, Free as in Freedom Software, and the Web pre-1.0 back in the ’90s while working as an ASIC/FPGA designer in Italy, Sweden, and Silicon Valley. This led to tech writing, including but not limited to hundreds of Free/Open Source tutorials. Over time, this odd combination of experiences has made Marco think way too much about the intersection of tech, ethics, and common sense, turning him into an independent scholar of “Human/digital studies” who yearns for a world with less, but much better, much more open and much more sensible tech than we have today.

The entire US gun control industry is fighting against human nature, reality (see “gun free zones”) while attempting to disarm the US public. Europe has it’s own numerous issues when it comes to firearms. (See as an example the UK, which basically banned most firearm ownership, only to now have to focus on banning knives. Next up banning pointy sticks. Then rocks.).

The need for self-defense is ever present and the vast majority of legal – stressing legal – firearm owners in the US are above and beyond reproach in their seriousness and safety focus. I carry a firearm regularly myself. And I can firmly state that If the left ever seriously attempted to enact and conduct a nation-wide gun ban they would be met with utter scorn, “Irish democracy” and sheer massive disregard for such laws. (See. e.g., compliance in NY and CT when each state banned AR-15, subject to grandfathered registration. The level of registration compliance was on the order of 4%).

As you note a better path would be to working on tuning and upping the civil culture and societal norms in general (yet another area where the left has worked diligently for decades to undermine). The bottomline is that the left has lost the gun war, except in pure blue holdouts like NYC/NYS, CT, Illinois and California. Post Covid gun ownership has risen and it has risen fastest among women and in particular black women (facts that the left can’t stomach).

As I understand it from here, both the US left and the US right (which would be called “right” and “even more right” in many other place, but that’s another issue) have worked diligently to undermine american civil culture and societal norms on many issues, not just gun control.

So yes, both parties should cooperate to “tune and up” that culture and those norms. The same could be said, of course, for many other countries (except for gun control which is a uniquely US problem).

Mr. Fioretti, you do speak much like many White Europeans speak, as I lived in Europe for a few years. I, however, am not a White European, so perhaps this perspective may add to your view.

I am a racial minority in the United States, specifically Black and Native (i. e. Indigenous) American. If you read about the history of gun control here in the United States and really do a study on it, you will find that it was created to keep Whites armed, but disarm those who are not White. California’s gun control legal regime was aimed squarely at Black freedom activists due to repeated “Rodney King-style” beat-downs by the (virtually entirely White) police forces. That California legal regime is called the Mulford Act, enacted by both Democrats and Republicans virtually unanimously. After the law’s enactment, White police officers regularly continued to recommend guns to White families for self-defense, informing said families that “that new law wasn’t meant for you!”

The Deacons for Defense, who defended the Selma marchers with Martin Luther King, Jr., were also armed. That’s the only way they could defend themselves from Ku Klux Klan-aligned racist police. That event, among others, shows us that yes, racial minorities being armed did reduce the beat-downs.

Today, we continue to see police disproportionally harassing racial minorities here, in various forms. The murder of George Floyd by former officer Derek Chauvin is just one example of many, and sadly, this is not an “isolated inicident”. And then, of course, there’s Tiananmen Square and situations like that, where “only the police and military have the guns”.

This is the problem with gun control. This is also the problem with registration, which as we’ve seen time and again, leads to confiscation. That’s why 3-D, so-called “untraceable” guns are actually important, and it’s for the defense of freedom. The government never should know where all the guns are, and it’s for these reasons.

The question isn’t, and never has been, “how to protect against 3D-printed guns”. Rather, it’s how to get people less likely to commit violence, of any sort, in the first place, in a free society. And that is the question that really must be front-and-center. It is unfortunate that, here in the USA, that question isn’t the one that’s front-and-center.

To Mr. Sum Yung Gai:

first, thanks for your comment. I do know, albeit not in depth, about the interconnections between gun control policies and racial issues in the US. What you call “how to get people less likely to commit violence, of any sort, in the first place, in a free society” is exactly what I mean when I suggest “developing social policies that would make more people stop wanting to kill others”. Let’s hope we come to see them.

You can try.

Look up the 2nd Amendment, specifically the “shall not be infringed” part.

This is not a dictatorship, not a “democracy”, no matter how loud the democrats, and the socialist democrats scream. It is a constitutional republic. The Constitution of the United States of America is the law of the land.

You are not an American, so your stance on law abiding citizens is expected. For ages, Europeans were indoctrinated that owning a gun is bad and if they give up their guns they would be safer, and they were told criminals would be scared of gun laws and would also surrender their guns. Reality begs to differ.

The latest mass shootings in Serbia and others proves that narrative wrong.

In the US a lot of times good guys with guns stopped certain massacres from happening.

That’s basic common sense.

Please stop trying to influence US politics and culture. You are not relevant to any of them.

Look at your European countries, People are getting arrested for posting their opinion on social media. That is the end result of supporting tyrannical and totalitarian policies like gun grabbing.

To John Smith:

Here in Europe, or EU at least, there are no ICE-like officers arresting and deporting citizens simply because they or their parents were born somewhere else.

In general, your comments about Europe, especially the last two lines, demonstrate you know Europe much less than I know the US. And that happens because I am still FORCED to care about US politics and culture, and hope that certain parts of them are never imported here. See https://stop.zona-m.net/2020/09/the-unbearable-us-ness-of-online-discourse/

Banning guns has never been about stopping people killing other people. It has always been about government repression.

If someone wants to kill innocent people you won’t stop them. A vehicle, a bomb, knives and all kinds of other options. When terrorist drive a truck through a crowded market killing an maiming a lot of people we don’t call for truck control.

Were people in the Soviet Union safer when the Bolsheviks took away their guns? No

No, you don’t know about the US, and I know more about Europe than you would ever know about the US, but you can try.

Contrary to what you believe, I visit the UK, France, Italy, almost every year.

I also visited Hungary and Poland, plan to go to Austria and Switzerland, time permitting.

So please continue to assume stuff about me.

Your article was about guns and banning them. What has your comment got to do with the argument?

You could not come up with an answer, so you decided to deflect and bring yet another debunked narrative.

“Here in Europe, or EU at least, there are no ICE-like officers arresting and deporting citizens simply because they or their parents were born somewhere else.”

Actually, you have the UK now deporting criminal aliens.

In the US, it is AGAINST the law to cross the border illegally, it is a misdemeanor, and repeat offenses become felony.

There is not one citizen being arrested or deported because their parents were born somewhere else.

Why post falsehoods?

Those arrested and being removed are the ones who have detainer/removal orders, those who criminal history in addition to their crime of crossing the border illegally.

Not one person who is a US citizen was deported. There will always be mistakes, but the couple of mistaken identity cases were corrected, and yet you make it sound like this is a routine thing.

Your link is to a random anti-US rant. Not really an argument, nor something intelligent in it.

You want to talk how “good” your EU countries are? How good the UK is?

You are seeing citizens arrested for the “crime” of posting something “offensive”, elderly are arrested for silently praying 100s of meters outside abortion clinics.

Why is that? How come your governments are getting away with such blatant violations of basic God given right to humans, free speech?

That right does not come from the gov, it comes from God. In the US, in the Deceleration of Independence, such rights are stated as inalienable right. I encourage you to research it, and then read the Constitution of the United States of America, after setting your irrational hate of everything US aside for a couple of hours.

Specifically read the 1s, 2nd, 4th, 5th, 6th, and the 10th Amendments, and you’ll understand why the US is the most powerful country in the world. Those rights, while at times some leftists try to violate, are protected. That’s what it is about.

But again, why you turned this into “I hate the US and I will post random debunked narratives” rather than answering on point, You published an article blatantly urging the violation of law abiding US citizens” right to bear arms, which is protected under the 2nd Amendment of the Constitution, and when shown facts, and your motive was questioned, you ignored all that, brought up irrelevant argument about ICE which you, again, show a clear lack of understand of basic US laws.

But isn’t this great? You publish such an article, if that was in your beloved EU, urging violation of laws, you’d have been in legal hot water by now, but in the US that you seem to hate, you are still protected by our 1st Amendment, which part of it guarantees freedom of speech, and protects you from government going after you for posting your opinion.

You can hate the US, and post false narratives all you want, reality and facts are not the same as your opinion, or your feelings.

At the end of the day, I wish you well, and hope you educate yourself on the US before posting such article(s) about it.

(You may resort to censoring this response. By doing so, you prove again everything said.)

Again to Mr. John Smith:

You visited some European countries, I’ve lived in the US a few years.

Again to John Smith:

You visited some european countries. I lived in the US a few years.

About ICE: according to the most american search engine there is, “The American Immigration Council reports that at least 2,840 US citizens were wrongly identified by ICE as non-citizens. … ICE has been known to deport individuals with pending legal cases, preventing them from having their day in court to prove their right to remain in the US. … A significant percentage of those deported by ICE have no criminal convictions, and some have only minor infractions, or even no charges at all, according to the Cato Institute.

etc. etc.

ALSO, my “irrationale hate of everything US” only exists in your head. There are certain things I do not like about the US, the mainstream attitude about guns being one of them. There are also many other things I like about the US, and wish Europe could imitate, but they are not stuff that would interest FOSS Force readers, that’s why you’ll never see me write about them here.

So, just to save everybody’s time, let’s take my ICE comment simply as a reminder that no country is perfect, and let’s limit further comments to gun control.

On that score, the article I’ve published here only explains why and how certain specific policies for control of 3D printed guns cannot work period, regardless of what one thinks of gun control in general, of who proposes them, and of which country they should be applied in. Do you agree?

To “Responsible Gun Owner”, about: “Banning guns has never been about stopping people killing other people. It has always been about government repression.”

I do know about the US Second Amendment, and the argument about guns against government repression. It doesn’t change the fact that school shooting or mass shootings in general have been a uniquely US phenomenon until very, very recently (UToya being the exception that proves the rule), which is why in the article I propose “developing social policies that would make more people stop wanting to kill others” as much more effective measures than ridiculous bans on gun blueprints, or on 3D printers that could use them.

“ALSO, my “irrationale hate of everything US” only exists in your head. ”

Well, Mr. Fioretti, thanks for turning this into a flow of personal attacks.

You’ll notice that I never made a comment about you personally.

I can only call things as I see them. I did not make that up. The link you provided was from you griping about someone telling you that you are irrelevant to the US politics, not being a permanent US resident/US citizen. That is like me being relevant to Italy politics.

You claim that since you allegedly lived in the US, then that makes you an expert on US politics.

Really?

That’s even a weaker argument.

Also, I don’t only visit European countries regularly, I have family members living in the UK, France, and Italy.

A large family stretching globally.

We often discuss politics and social issues, culture and that includes gun ownership discussion.

So you will not be able to prove that you know about the US politics more than I know about European/UK politics. Your argument falls apart given the statements you made so far.

Your cited sources are discredited. All on the far-left side of politics, activist nonsense. Period.

Plus, citing Cato Institute? Really? The accused of connections to China?

Find a better a source. Or at least, find a source that is pretending to be independent.

These people claimed US citizens were deported under Bush43 and during during Trump’s first term.

All were discredited.

It is a solid case of “The boy who cried wolf” all over again.

I encourage you to read that reference.

You really are arguing, the law-suit happy far-left activists here in the US are sitting on such violation of US citizen rights, and did not take that all the way to the Supreme Court?

Who are you trying to fool here?

Read clearly what I said. I said mistakes always happen. Mistakes will always happen, but there was not ONE US citizen that was deported. That was your claim, remember?

Now suddenly you shifted the narrative from “US citizens are being deported”, to “US citizens misidentified as illegal aliens, according to shady sources that I trust”, which is incredible to see.

Why not just admit that you made a mistake and move on?

“So, just to save everybody’s time, let’s take my ICE comment simply as a reminder that no country is perfect, and let’s limit further comments to gun control.”

No one brought up ICE and deportations. You did. When that was challenged, you responded with more debunked narrative and talking points of the far-left in the US.

Now you suddenly want to shift back to the gun control argument, that you brought up on a site that is supposed to be be all about for free and open source software.

Amazingly, in another comment, you say

“I do know about the US Second Amendment, and the argument about guns against government repression. It doesn’t change the fact that school shooting or mass shootings in general have been a uniquely US ”

For someone who claims to know about the 2nd Amendment, you are arguing against it. Urging violation of rights that are guaranteed in it.

I guess you are unable to read your own words, or just refuse to do so.

Also, you are wrong. The school mass shootings are not unique to the US. A recent example was in Serbia.

You only hear more about it in the US because the left controlled mainstream media (which has the lowest favorability among US citizens) work as a mouthpiece of the democrats and the far-left who are bent on taking down the 2nd Amendment rights to the US. The DNC elected vice chair campaigned on taking down the 2nd Amendment (he can try), and on social media, his statements often were labeled as out of touch and dangerous, arguing that the 2nd Amendment does not guarantee the right to bear arms, even though it explicitly states so, and adds that it cannot be infringed, and despite the landmark ruling of DC vs. Heller in which the Supreme Court, again, affirmed the 2nd Amendment, that never stopped the left from wanting to take the 2nd Amendment down, because it stands in their way of a totalitarian control.

Your precious European countries are arresting citizens for “offensive” speech on social media, in Germany, they are arresting people for “lying”, and in the UK peaceful praying across the street from abortion clincics landed elderly Christian grandmother in jail, one of dozens who got arrested for silent prayer for the unborn being murdered.

Why is that? Why they can’t do that in the US? They have tried, and it did not end well for those who tried to stifle free speech and the right to practice religion.

Why do you think European countries are able to get away with that authoritarian nonsense?

How convenient for you to ignore responding to this point made, even through you chose to respond to everything else.

Because you know the answer. No government would dare to do that to its citizens if they are armed.

You know who else shares your “vision” about guns?

Every tyrant throughout history.

How did the Armenian Genocide happen?

How did Germany in 1935 enact the Nuremberg race laws? What happened after that?

How did Soviet Russian control the masses?

How did the Cambodian genocide happen?

How did “cultural revolution” happen in China?

What do all those tyrants have in common?

They all grabbed guns and outlawed them before committing the atrocities.

Here in the US, since you think you know its history, look up the Wounded Knee massacre of the Red Indians. They were told to surrender their weapons and the gov would protect them. Immediately after doing so, they were massacred.

There are more lessons in history that you seem to have ignored or missed.

The governments do not look for your interests. They look to control you.

Criminals would not surrender their guns. They don’t abide by gun control laws, nor give a rip about it.

They are called criminals for a reason. They don’t abide by laws.

Gun free zones proven to be a favorite target for mass shooters, schools included. Ever stopped to think why? Because they know no one armed would be there to stop them.

Look up who was behind the bill for gun free zones?

It was democrat Joe Biden, with a full support by his party behind him.

Your published article urges violation of constitutional rights guaranteed in the 2nd Amendment. It will fail. All attempts to infringe on such rights failed.

Some still being litigated and they might go all the way to the Supreme Court and they will be struck down as unconstitutional.

As I said in a previous comment, you can try, but it won’t go anywhere.

I encourage you to educate yourself more about the US, rather than irrationally hating it, and then denying you do so.

Read the US Constitution. It is not that complicated. It is in clear English.

To understand it, read the Federalist Papers, and the documents from the Constitutional Convention. The Founding Fathers explained why they chose to make the US a constitutional republic and not a demcoracy, as they accurately labeled the latter tyranny of the majority, and why they put the right to bear arms and guaranteed it in the Constitution.

The problem with your argument, and why all the comments from those who responded argued against your article is that you are sharing your opinion on US politics and constitutional rights wearing your leftist European glasses.

That does not work here.

We fought for our independence for that exact reason.

Worry about your European counties which are out of control. Soon, you’ll be a minority in your own country and your leaders surrendered sovereignty and convinced you that you will be safer if you trust them and abandon your basic rights.

The US may not be perfect, but it is the best country in the world, and it is only a matter of time before you’d need to help you get rid of the next evil rising in Europe, and I pray that won’t happen, but if you have read history and paid attention, you’d see similar environment that led to the rise of evil in the 1930s and how that ended.

You can push for gun control all you want. The only people in the US who would agree with you are the marxists and those who never did their homework and never read, or ignored history.

The majority have spoken on this issue. There are over 130 million law abiding legal gun owners in America today, and the numbers are going up.

That’s reality.

To John Smith:

Here on Foss Force, I will STOP to one small part of last comment, since I have a deadline today, and this is not the place to give you a full answer anyway:

““ALSO, my “irrationale hate of everything US” only exists in your head. ” Well, Mr. Fioretti, thanks for turning this into a flow of personal attacks. You’ll notice that I never made a comment about you personally.”

I sincerely apologize for having the gall to doubt that you know everything in my head better than myself. However, saying “You claim that since you allegedly lived in the US” is exactly that, an implicit comment about my credibility.

That’s all I have to say here and now. I do hope, however, to give your full comments all the detailed answers they indeed deserve sometime soon through my newsletter at https://mfioretti.substack.com

“I sincerely apologize for having the gall to doubt that you know everything in my head better than myself.”

You are just be disingenuous at this point.

That was not what I argued again.

I argued that you hate the US, have contempt to everything American given your own words, and your provided link to your rants about an incident in 2020 when someone rightfully told you to mind your own business and that you are irrelevant to US politics. A comment that you brought on yourself and richly deserve, given your entitled attitude and assumption that you have the higher moral ground.

“However, saying “You claim that since you allegedly lived in the US” is exactly that, an implicit comment about my credibility. ”

Yes, your credibility is questioned at this point, and that is saying it nicely. Saying questioning your credibility on the US, US politics, gun rights, and the 2nd Amendment is part of the debate. That’s something normal here in the US. If you are saying questioning someone’s qualifications and credibility is a personal attack which is equal to your disgraceful personal attack, then you are again, being disingenuous, or simply don’t understand those concepts.

Maybe it is the language barrier, I’ll give you that, but I doubt it.

Questioning credibility and relevance is part of court systems everywhere. Are you saying that is a personal attack? If so, why are courts allowing them then?

It is not.

You got caught posting nonsense, and got called out for turning the discussion from a debate over gun rights, something you, a non-US citizen think you have a say on it, then turned it into a false narrative about US citizens being deported, and when both were debunked and blown to smithereens, you resorted to personal attacks. I knew this would be the end result of yet again, trying to debate a liberal/leftist on such topics. Since none of you stand on principle, your best shot at winning the argument, in your mind, is to deflect, and if that fails, to resort to personal attacks.

You posted this article. I did not.

You responded to my comment reminding you of the 2nd Amendment, by deflecting to the false narrative of how US citizens are being deporting. Something proven false again and again.

Then you shared that link of your anti America rants.

I did not make up stuff. I used your own words against you.

Then you turned this all into personal attacks, rather than either provide intelligent counter argument, like most of responsible adults do, or just admit that you were wrong and gracefully exit the conversation. I was wrong in the past, many times, and when I realized I was wrong, I posted saying, and exited the conversation and used it to learn and acquire more knowledge on the topic.

But that seems to be not the case with you here.

You doubled down on your hate and then played the victim of an attack that never happened on you personally.

Here in the US, we call this professional victimhood.

Once you lose the argument, throw random accusations and pretend to be the victim.

Not exactly unexpected.

And no, I am not interested in reading more of your anti America drivel from your “newsletter”, where you have a one way conversation.

You lost the argument here and your only resort is to go and fume more on a platform that you either have no opposing voice to counter your nonsense, or have an echo chamber of your fellow America haters.

You can enjoy your newsletter and hearing the echo of your own rants there.

You have ZERO credibility when it comes to the US, the US politics, the US culture in general and gun rights. That will not change. You are irrelevant to all that. You can say what you want, but no one will take you seriously, and at best, you will get rebuked by US citizens the way you got here.

I am done reading your nonsense.