Not all open source is created equal, argues open source advocate, Nextcloud co-founder, and FOSS Force guest writer Jos Poortvliet.

Free software licenses were conceived as a way to move power from software providers to users, but this burden is often too much for the license alone. There are plenty of ways in which an open source project can be less free than its license suggests, but how do you tell? One way is through a new website, Is It Really FOSS, which aims to provide users with insight into the actual freedom they can expect from a project advertising itself as open source.

I think this is important, and I think you should care. Here’s why.

License Shenanigans

The free and open source ecosystem features a dizzying array of licenses. Some veer more towards copyleft, meaning they strictly follow the four freedoms set out by Richard Stallman in the ’80s. The “permissive” licenses, are more “do as you will,” and allow the inclusion of their code within proprietary projects with few or no limitations. Others try to look like open source licenses, and sometimes even claim to be open source, but they don’t fit the definition and aren’t compatible with legitimate open source licenses.

Recently, a few new licenses have appeared in the latter category that restrict certain use cases, usually with the purpose of helping the businesses behind those projects block companies like Amazon Web Services from profiting from the software without contributing back.

Those restrictions automatically mean the license isn’t open source, according to Open Source Initiative, the organization that determines whether licenses are legitimately open source according to a definition they adopted in the 1990s. Putting restrictions on use is but one thing that’s not allowed, because open source means — by definition — that you’re free to use the software in any way that you like.

So, does that mean that having an open source license makes you good-to-go?

Let’s have a look. I will paint a portrait of three fictitious products here, all building similar products and each with an open source license, to illustrate why users need to consider more than just the license when choosing software.

A Tale of Three Projects

Project 1 is developed by Company A, which issues a new release every six months. The source code, licensed under the GPL, is published as a zip file on the community page, allowing users to download, compile, and run it as they wish. The company also offers a proprietary enterprise edition with features that are not available in the open-source version. While a user forum is provided for product discussions, development is otherwise closed. Issues can be reported in the forums, though developer engagement there is limited.

Project 2 is developed by Company B, also using the GPL license, with development happening in its GitHub repository. Frequently, features are dropped as big code drops, but it is possible to do pull requests after signing a contributor license agreement or applying a permissive MIT/BSD-style license to the contributed code. GitHub also contains the build scripts needed to test your contribution, and indeed, occasionally people contribute fixes.

Project 3 is developed by company C, also under the GPL. Development is in GitHub, and besides the 60 engineers, about 150 others contribute regularly. There is no CLA, but the company does have an Enterprise edition of its product. It is built from the same code as the community version, but has differences in versions, configuration, and some features.

Imagine now that you deployed one of these three projects and the company behind it takes a direction you — and many other users — don’t appreciate. Perhaps the company was purchased, maybe went bankrupt, or just added features people didn’t like. What are options do you have? In all three cases, customers and users have the option to get together and chart a new path forward, because that’s a right the GPL provides. But if they make that decision, their chances of success are vastly different, depending on the project.

To fork, you need three things to be as easy as possible:

- Access to the code: Project 1 and 2 have proprietary, enterprise-only features, so you will have to re-develop these.

- Ability to build the code: Project 2 and 3 have build scripts and instructions, but Project 1 does not. This will need to be developed.

- Access to a pool of developers familiar with the code: In Project 2, people have looked at the code and you can expect at least some minimal documentation to be in place. Project 3, of course,takes the crown – with 150 contributors it should have a wealth of documentation, tutorials, and more to help onboard new contributors. Also, existing and past contributors might be available for hire!

Even More Variables

There are many more scenarios possible. Licenses can be different — counter-intuitively, a BSD or MIT style license for Project 3 (the fully open one) would allow that company to have proprietary features only in its enterprise product, making a fork more difficult. It’s also possible that multiple companies contribute to the project – as with the Linux kernel. In that case, a fork is much easier. Last but not least – perhaps the project has no company involved at all. Would that make forking easier?

Actually, not really. In that case, there is likely no viable business model, so splitting the available resources — be it volunteer or donation-based — would likely slow down the fork and its original project.

Should You Fork?

A fork nearly always reduces the resources going into a project. Because many forks fail, and others end up damaging both projects, forking should be a last resort. Even successful forks, like the LibreOffice fork from OpenOffice, can take a decade or longer to really catch up. Situations like OpenWRT — a distro for Wi-Fi routers that was forked as LEDE in 2016 and merged back into the project in 2018 — are rare.

Besides, you don’t always have to fork. For instance, in our example Projects 2 and 3, it’s possible to contribute features and improvements. In the case of Project 3, even if a feature would result in a serious maintenance load that makes the maintainers unwilling to pick it up, it’s possible that a community member might be allowed to maintain the feature.

However, that doesn’t mean the ability to fork isn’t deeply important. The risk of a fork provides a strong incentive to communities and companies around open source projects to stay aligned with the needs of their users and contributors.”

In the three scenarios I laid out earlier, which organization do you think is most likely to act in the wider community’s and users’ best interest? To me, the obvious answer is Project 3, and not only because it’s more aware of its community needs, due to the direct connection between its engineers and its community. The cost of a fork is larger, too: these 150 contributors make a significant difference to their development. Surely the wider community also cares and advocates more for their product — after all, it is a model of shared ownership.

Is It Really FOSS?

If you didn’t already know, by now you’ve likely realized that not only do open source licenses differ, but there can also be significant differences in the openness of open source projects, even when they’re developing software under the same license.

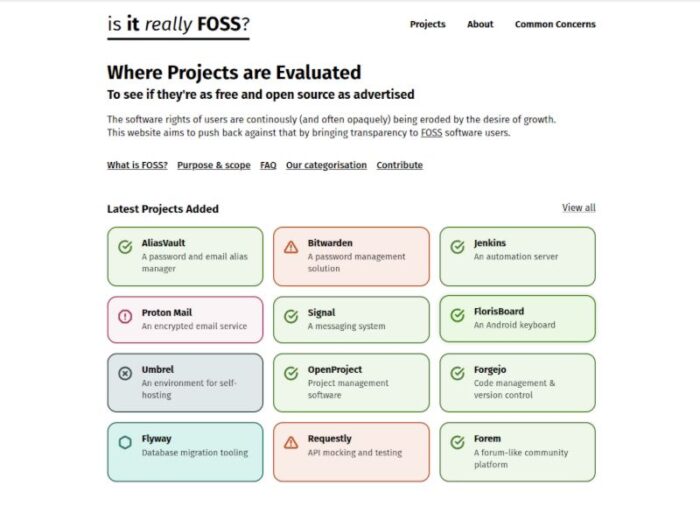

You don’t have to be confused, however, because there are resources to help hone your understanding—including a website called Is It Really FOSS, which went online recently. Here, you’ll find a community-maintained list of open source projects that rates them according to their level of openness. In each listing you’ll find information on the project’s license, development, openness, business model, and more.

The site is the brainchild of UK-based developer Dan Brown, who tirelessly — and with great attention to detail — maintains and grows the list.

If you are relying on open source products, be it as a library in your own project or as a user, it pays to have a look at the project behind it. Remember, don’t just look at the license, but also check its openness, the funding model’s sustainability, and the extent of contributions from outside the core team. Sustainable open source projects are those that meaningfully share ownership with a community, not just use the license as a marketing tool.

Jos Poortvliet is co-founder and Communications Director at Nextcloud. He is a long time technology enthusiast and all-things-open evangelist. He has previously been community manager at SUSE and worked as business consultant at government, finance and telecom companies in the Netherlands. He is based in Berlin and loves cooking for friends, family and colleagues.