The Austrian Ministry for Economic Affairs drops foreign clouds for a homegrown Nextcloud and LibreOffice solution, showing Europe’s steady move toward digital independence.

Great news about open source adoption came out of the Nextcloud Enterprise Day Copenhagen 2025 event on Wednesday. BMWET — the Austrian Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs, Energy and Tourism — has made a major shift away from foreign owned and operated clouds and proprietary SaaS services to a home grown IT infrastructure centered on Nextcloud, along with Collabora, which runs on Nextcloud and offers the LibreOffice productivity suite as a user-hosted service.

The good news here, from an open source perspective, is that this isn’t some pie-in-the-sky plan that will see fruition at a future date. This one’s already in the can. It’s a done deal.

“We’re very excited about this case because it shows that, with some courage, you can get great results,” Nextcloud co-founder and director of communications Jos Poortvliet told FOSS Force shortly after the announcement was made.

“Many people in especially large organizations worry about the impact of replacing big tech solutions with open source collaboration technology,” he continued, “both in terms of the effort it takes and user experience. Austria showed that with some clever moves you can regain a lot of control with minimal user impact and in a very short period of time.”

Digital Sovereignty Becoming a EU Reality

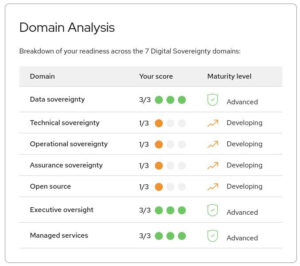

The move is all about digital sovereignty, which for the last few years has been a catchphrase in European discussions concerning the intersection of tech and jurisprudence. Simply put, digital sovereignty is the idea that a country should be able to govern how data about its citizens is collected, stored, and processed to create what is essentially a “what happens in Vegas stays in Vegas” approach to information control.

“Digital sovereignty is a key requirement for Europe’s future,” Nextcloud co-founder and CEO Frank Karlitschek said in a statement about Austria’s move, which was prompted by a risk analysis showing that overseas cloud offers failed to meet the ministry’s privacy requirements.

“The fact that the Austrian Ministry of Economic Affairs is taking the lead here is a strong signal to other public institutions to promote their own solutions and reduce dependencies,” Karlitschek continued. “That the implementation was completed within just a few months shows that even complex IT projects in public administration can be successfully realized with the right support.”

A Quick, Well-Planned Migration

To be precise, this project went from zero-to-sixty — that is, from proof of concept to being rolled out to the ministry’s workforce of 1,200 — in about four months. Many previous efforts in other jurisdictions to migrate workforces en masse from established proprietary applications such as Microsoft Office to open source alternatives have met with resistance, which either greatly slowed adoption or ended up stopping the attempt in its tracks.

Martin Ollrom, BMWET’s CIO, explained what made this project different:

“An extensive information campaign, clear communication, training, and a gradual transition ensured high acceptance and a smooth process,” he said in a statement. “By integrating the new solution into existing systems, we were able to modernize our digital service catalog and collaboration processes without changing established workflows.”

The part about integrating new solutions with existing systems might be key to this migration’s success. Some of BMWET’s existing licensed tech, notably Microsoft Teams, remains in use, even though it appears that the plan is to eventually phase those out as licenses expire. For the time being, according to an article by Nextcloud senior communications manager Kim Pohlmann, “Nextcloud handles internal collaboration and secure data management, while Teams remains available for external meetings.”

All Turtle and No Hare

Today’s announcement makes Austria something of a front-runner in Europe’s snail’s pace race to obtain digital sovereignty.

In September, the country’s military successfully completed the migration of all of its desktop systems — approximately 16,000 workstations — from Microsoft Office to LibreOffice. That move was also for the purpose of digital sovereignty, although there was also a financial angle at play: the migration will save the Austrian Armed Forces about $6.5 million in yearly license fees.

Much of Austria’s workforce remains uncovered, however. BMWET represents just a fraction of Austria’s public sector, and although its move — and the move by the armed forces — signals a federal‑level policy direction, it’s not a mandate that covers all government bodies. That said, it’s likely that this will influence other sectors of the Austrian government as the country moves toward a sovereign, EU‑controlled infrastructure in the coming years.

Austria is hardly alone in this move away from international clouds and closed-source proprietary software platforms that are largely controlled by the dictates of US interests. Notably, the German state Schleswig-Holstein has largely completed an effort to replace Microsoft Exchange, Outlook, and MS Office on the workstations and laptops of about 40,000 state employees with open‑source solutions such as Open‑Xchange, Thunderbird, LibreOffice, Nextcloud, and others.

There have been reports that the state has also been developing its own downstream version of the KDE Plasma desktop, as well as its own Linux distribution, based on openSUSE.

Contrary to some misconceptions, open source remains an important consideration in Munich as well. Although it famously shut down its LiMux Linux program in 2017 that it started with great fanfare in 2004 –and which once ran on thousands of the city’s workstations — the city council remains committed to open source, but focuses more now on open standards, interoperability, custom apps for local government, and contributions to public projects.

In 2024, the city established an Open Source Program Office, with a mandate to review software procurement, advise on open source policy, and ensure that publicly funded software remains available to all citizens.

Christine Hall has been a journalist since 1971. In 2001, she began writing a weekly consumer computer column and started covering Linux and FOSS in 2002 after making the switch to GNU/Linux. Follow her on Twitter: @BrideOfLinux